Rich Ostrander's miniature masterpieces

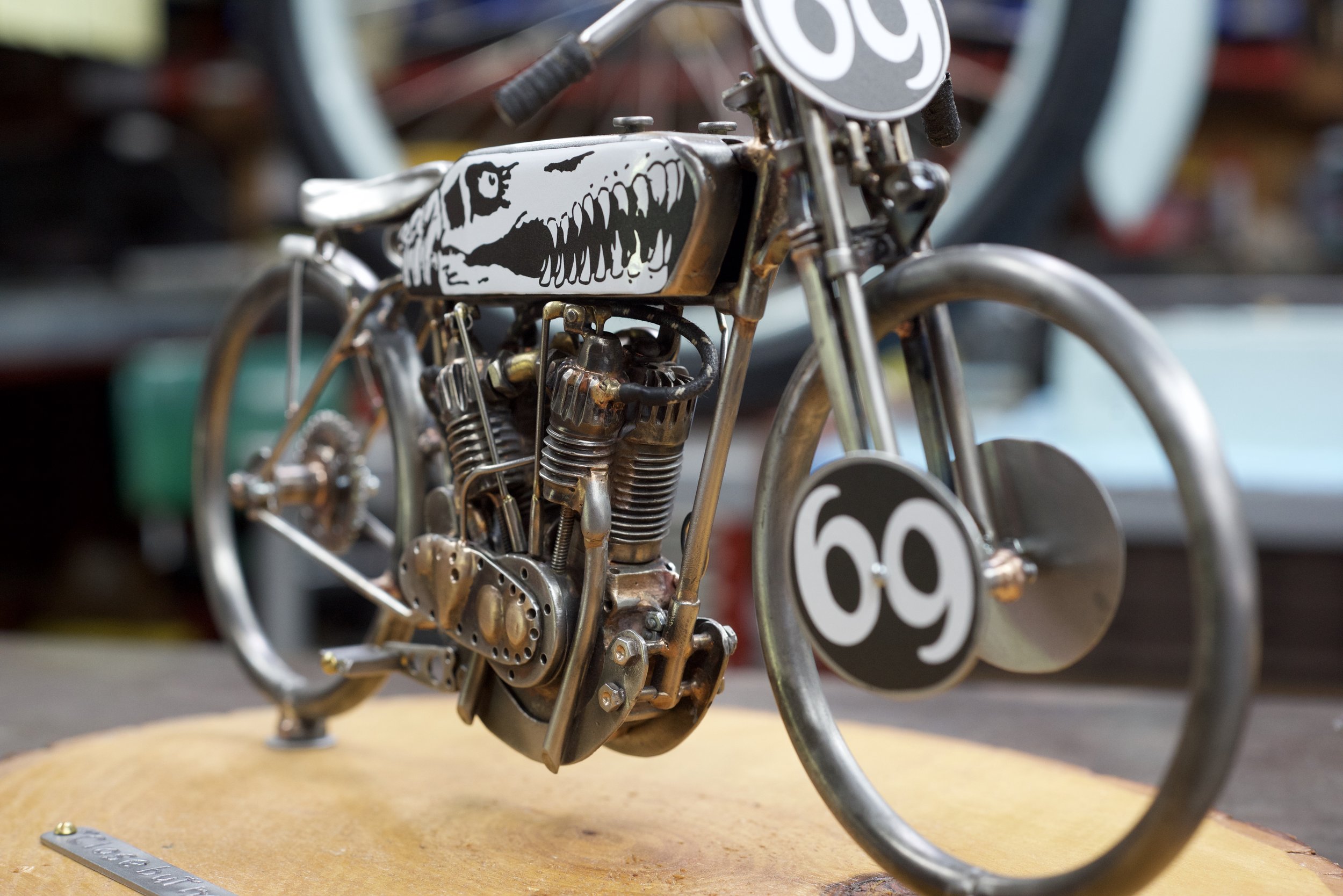

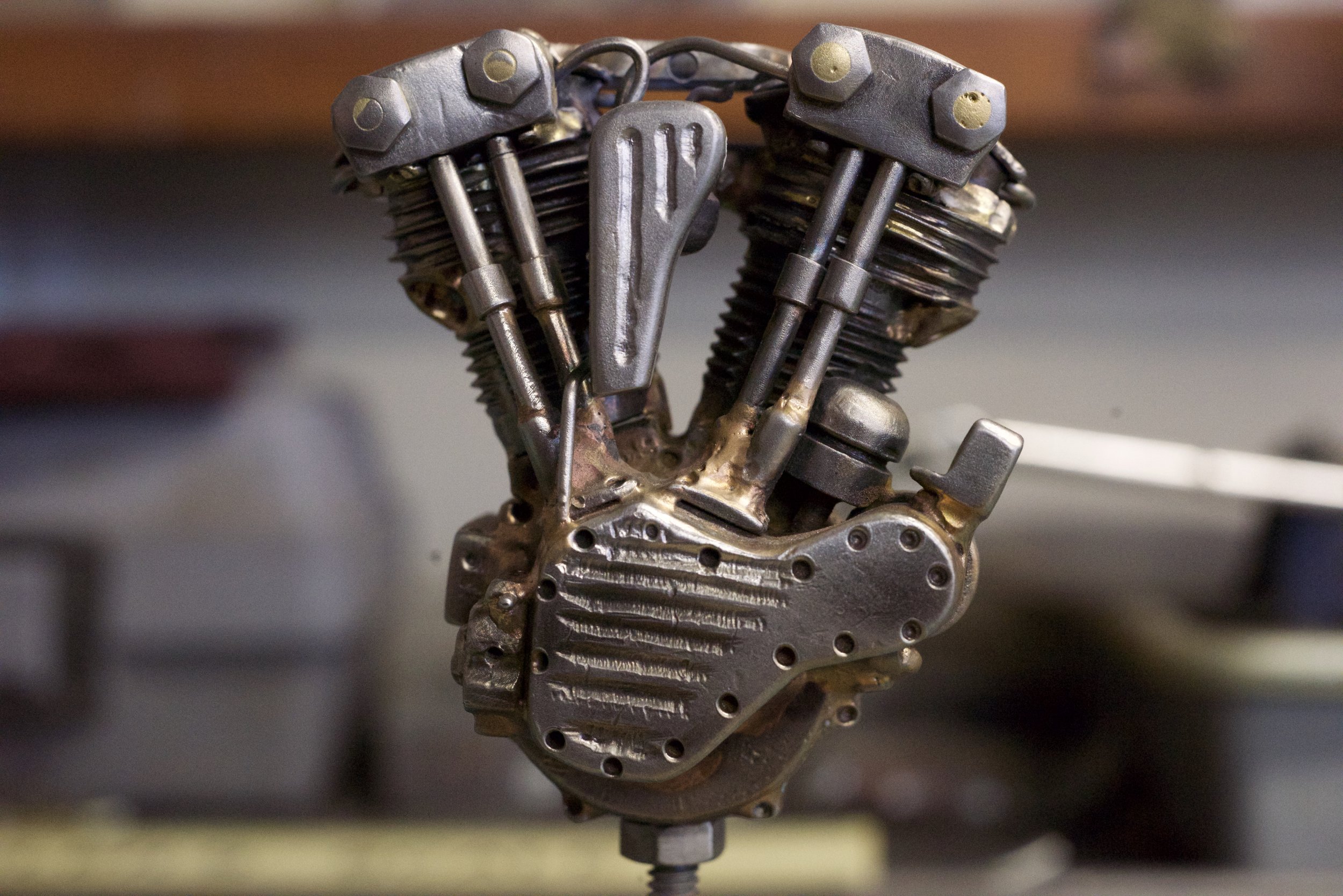

1920 Harley Davidson JD race bike. A huge amount of handwork goes into fashioning the engine components. Ostrander’s favorite tool is a die grinder with a cutoff wheel. The fins on the heads and cylinders are formed and shaped using this tool. If you have ever used a die grinder you will know how tricky this can be working with small pieces of metal. It’s easy to loose a chunk of finger.

Words+Photos: Mike Blanchard

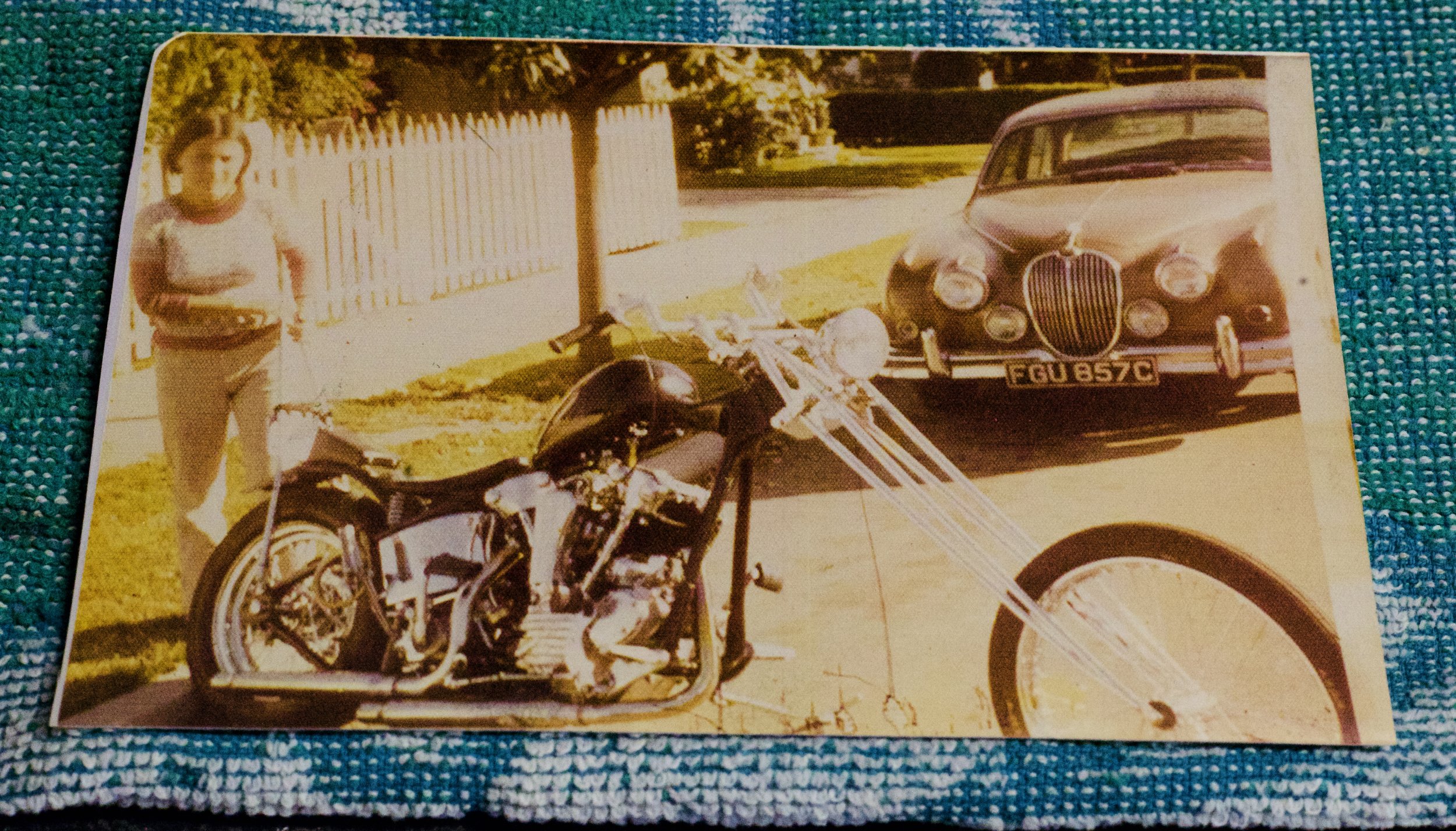

Rich Ostrander is a dyed-in-the-wool motorcycle guy. He has been riding since he was in high school, mostly vintage stuff. He has built and ridden bobbers, long bikes, antique bikes, even some Japanese and European bikes. He has ridden in rain, snow or sleet for years.

Some of you may know Rich as Dr. Sprocket. Under that nom de guerre he has produced numerous articles for moto magazines and websites all over the world, including Rust. He is a stalwart of the Fort Sutter chapter of the AMCA and the historian of the club. He is one of the most knowledgeable people on the history of motorcycling on the West Coast.

He is retired now, but in his professional life Ostrander was, among other things, a welder, fabricator, metal finisher and heavy-equipment repairman. He spent most of his professional career working with metal.

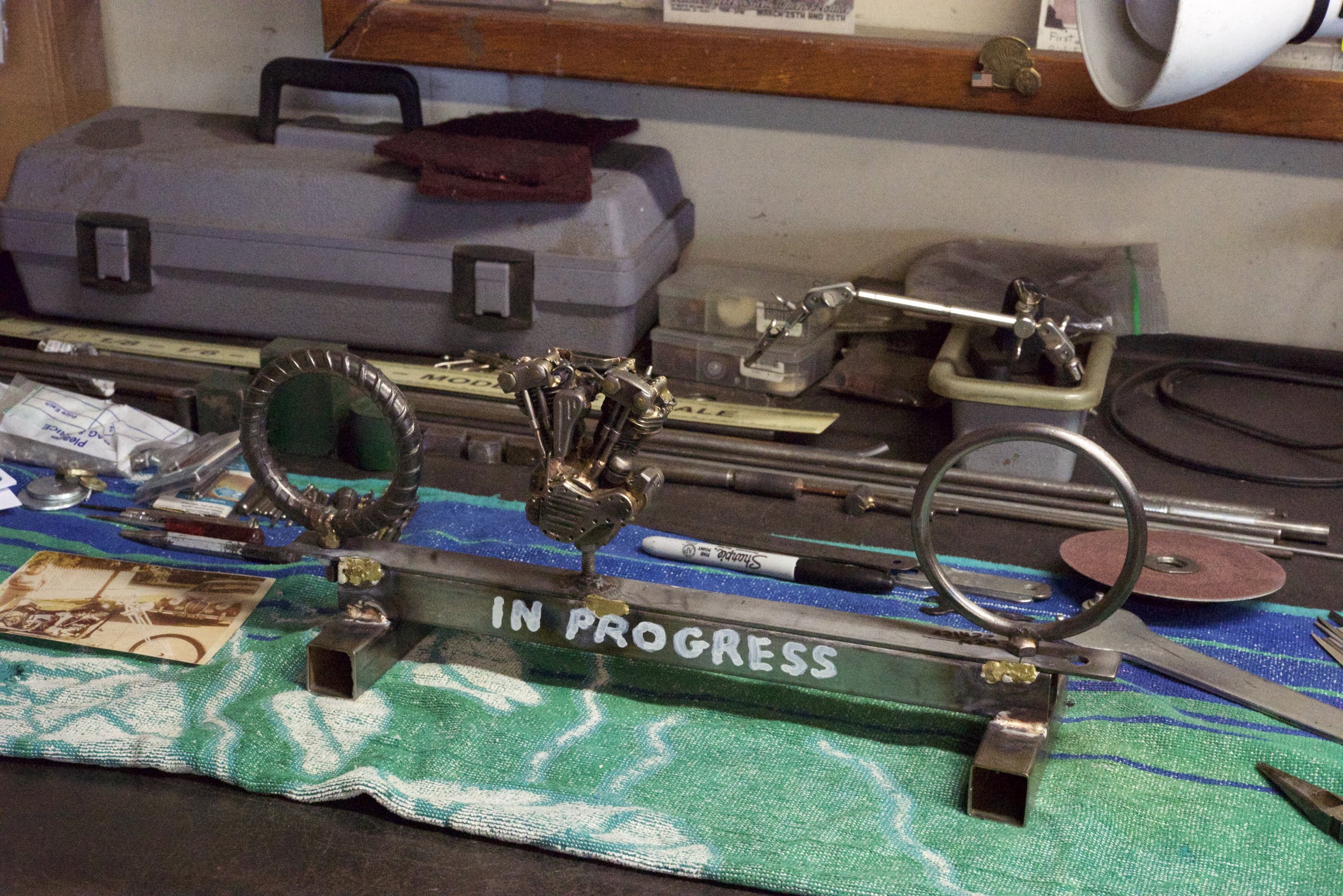

A few years ago, almost by accident, Ostrander began making sculptures. The first was a diorama of a welding shop intended as a trophy. The sculpture was entirely hand-fabricated from steel. Then a friend asked if he could do a sculpture of one of his bikes. One thing led to another and he is now working on his sixth sculpture.

The sculptures are 1:6 scale, and a great deal of time and effort goes into making sure that all the preparations are accurate. Each piece takes between 150 and 750 hours to make, so there has to be a certain amount of dedication and passion to get it done.

He hand-fabricates every piece. A lot of the work is done using a die grinder, his secret weapon. But needle files and hand tools are used throughout. Ostrander may spend days building a small piece that you might not notice at first but which is vital to the outcome of the sculpture.

The parts are so small that figuring out how to hold the piece while it is being shaped can be a problem. And then there is the challenge of brazing something very thin to a part that is a solid chunk of steel without burning up the thin piece.

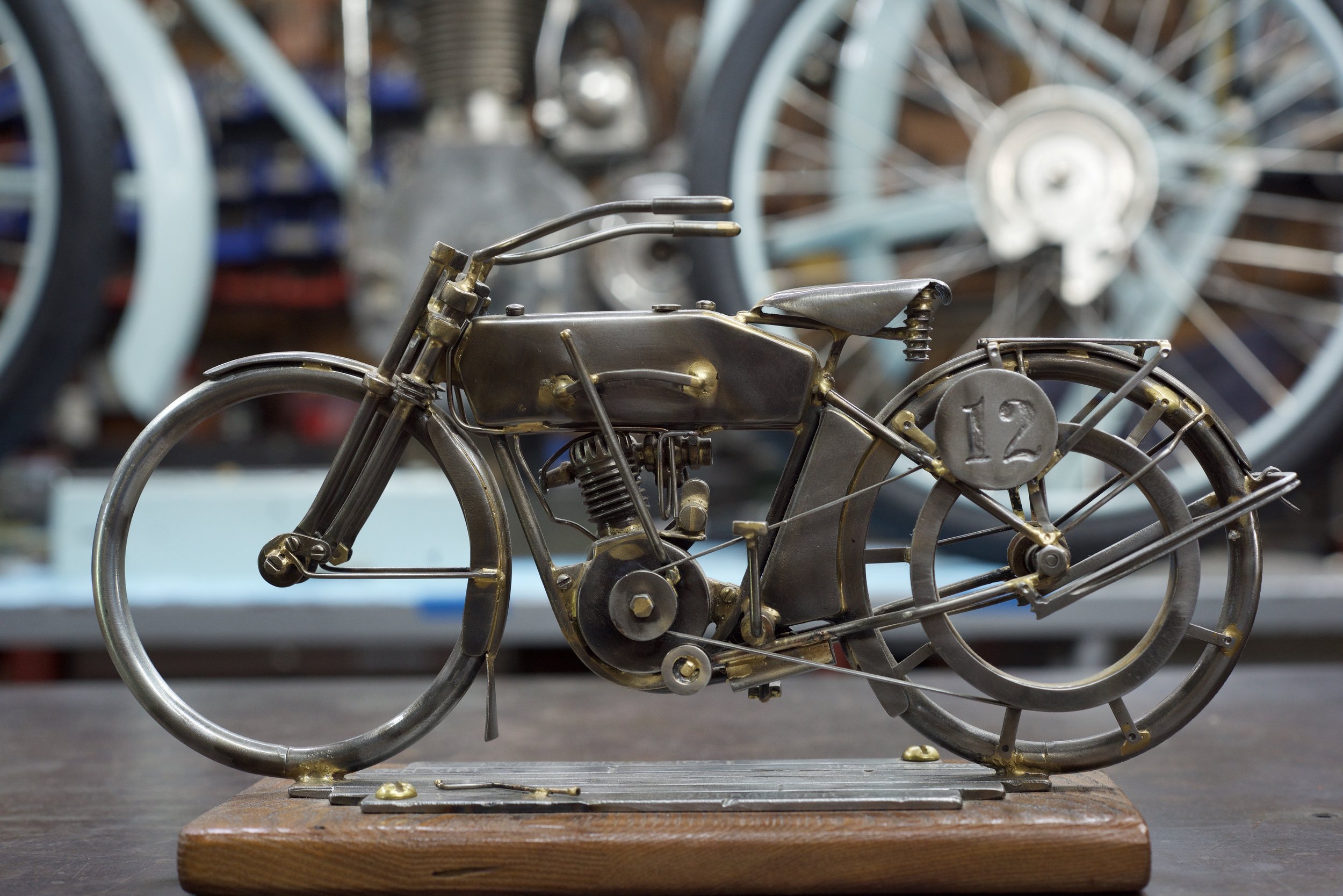

1912 belt-drive Harley Davidson single. This was the first motorcycle that Ostrander put together. It is a representation of the bike his friend rode cross country on the Cannonball Run.

Because the sculptures all represent actual bikes, it is important that they look right because the customer will know if it’s not. That is part of the challenge for Ostrander: to make it right. For a craftsman with motorcycles in his blood there is a lot of pride in getting it right, but more than that the process is clearly hugely satisfying to him.

“You have to be committed,” he says. “You have to be motivated to do this.”

Do you think of them as models or sculptures?

“I think of them as sculptures. I didn’t want them to be mechanically perfect, like using machines and lathes, or look like they would run. But I want them to be fairly accurate. I just want them to be a representation of what it (the bike) is.

“I do them from photographs and scale it to 1:6. My role model is Jeff Decker. He sculpts out of clay and then casts off of that, which is a hell of a lot different than taking raw material and making a miniature steel thing. I like the scale and the accuracy.

1915 Cyclone V-twin board track racer. The fuel tank is formed out of sheet steel over a hand carved buck.

“They are all made out of separate pieces and they’re all brazed together. They’re all steel. And they have the fuel lines on ’em and all the cylinders and all the bells and whistles and all the things they’re supposed to have.”

Do people commission you or do you just have an idea?

“The first one I did, I gave away as a trophy for Greasy Kulture … at Born Free for Best Modified. I made that welding station. I realized I could do stuff like that in miniature. So Dave Kafton said, ‘Could you make me my bike from the Cannonball?’ And that kind of started it off.”

What kinds of things do you make them out of?

“A lot of raw stock. From 1/16 and 1/8 inch round stock to 1/2 inch, a lot of bolts, pieces of bolts. The lower ends I use a cast iron fitting and then I’ll cut the sides off at the flanges and then I’ll put sheet metal on them and then put a hole through the center and that’ll be my crank pins that I attach stuff at the outsides. That gives me my center.

“Barrels and everything I’ll drill holes in them because I don’t want them to weigh so much.

“Most of the fenders and tanks I make bucks for. Either out of metal or out of wood and I beat the fenders on ’em. Then I carve a lot of stuff up or I’ll part it off. One of my favorite things is that little thing from … Harbor Freight, the little thing with the metal rod and the thumb screws that has the alligator clip to position stuff, and magnets, because you’ve got to position stuff to braze it, to hold stuff in position.

Beautiful details of the Harley front end. A lot of research goes into getting the details correct. The front forks are not as simple as they might appear to the layman. Ostrander does not add spokes. He feels the bikes don’t need them and it leaves something to the viewer’s imagination.

“The positioning is the real secret. … I make the base, then I get the wheelbase first, then I make the motor, frame and front end and then I fill it in.”

Have you found that you are getting more detailed or less?

“I made the ’12 Harley, the one he (Dave Kafton) took cross country, his little belt-drive single, that was the first motorcycle. I made that and it came out pretty good. But every one has come out better and better; I’m getting more detailed.

“One of the hardest parts of the process is getting the proportions of the bikes correct. It does not have to be off by much to look wrong.”

When he first started Ostrander took measurements off of photographs. He measured the size of the wheels and calculated everything else from that. But recently he has discovered the modeler’s scale: a ruler designed for scaling things up or down.

“I’ll put a photo in my copier and get it to 1:6 size. That gives me my scale. Then I can measure and do everything off of that. That (the modeling scale) helped me because I had to do tons and tons of math on my first two or three projects.”

Scale is super important on these sculptures, and even a small thing can make a big difference, as Ostrander found out in doing a commission for a woman who wanted a piece as a present for her boyfriend.

“I thought it was going to be one of his Knuckles; he had all these original paint Knuckles, so I start making a Knuckle frame. Well that’s 28 degrees, the Panhead is 29. So I’m making it and I go to put the front end on and it don’t reach and I realized that I had it at 28 degrees. I had to remake it from a Straight Leg into a Wishbone and I had to rake the front end out a degree on the 1:6 scale so the front end would fit because that’s how close I had it.”

So it doesn’t just come out of your mind. Do you make a drawing for each one?

“No, I’ll make a Xerox or whatever. Sometimes it can just be the frame and that gives me an idea. But mostly I just know the wheel size.”

It all starts with the wheels?

“Yeah, a wheel or a tank or whatever, that I can get a hold of. Or I’ll call Kafton and I’ll go, ‘Go out and measure the width of those handlebars’ and he’ll go, ‘They’re 34 inches,’ so I go to my scale, 34 inches, it’s like inch and a half. And then I know what to work with.

“I have to pinch myself sometimes. It’s not ego; I just surprise myself sometimes, I really do. I think I can do that and then I see it in my head and I start grabbing stuff and start putting it together and I have a process.

“There are some technical things. There are times I have to think about it. And that’s the fun part. Ha! How do I overcome the obstacle of making that little bastard? I have to think about that sometimes because you don’t want to screw it up. I mean you put an hour or two into some little petcock. Ha! The challenge of how do you put together? That’s the fun part.

“And then they’re done and they’re gone and you don’t see them. Very few people have seen my work. I’ll see them after a long period of time and I’ll think: ‘Goddamn! I can’t believe I made that.’”

A great lineup of sculptures. You can see they have become progressively more detailed. These pieces have been in a private collection their whole life so it is quite a treat to be able to show them to our readers.

Words+photos: Mike Blanchard