Notes on design by Jerry Blanchard

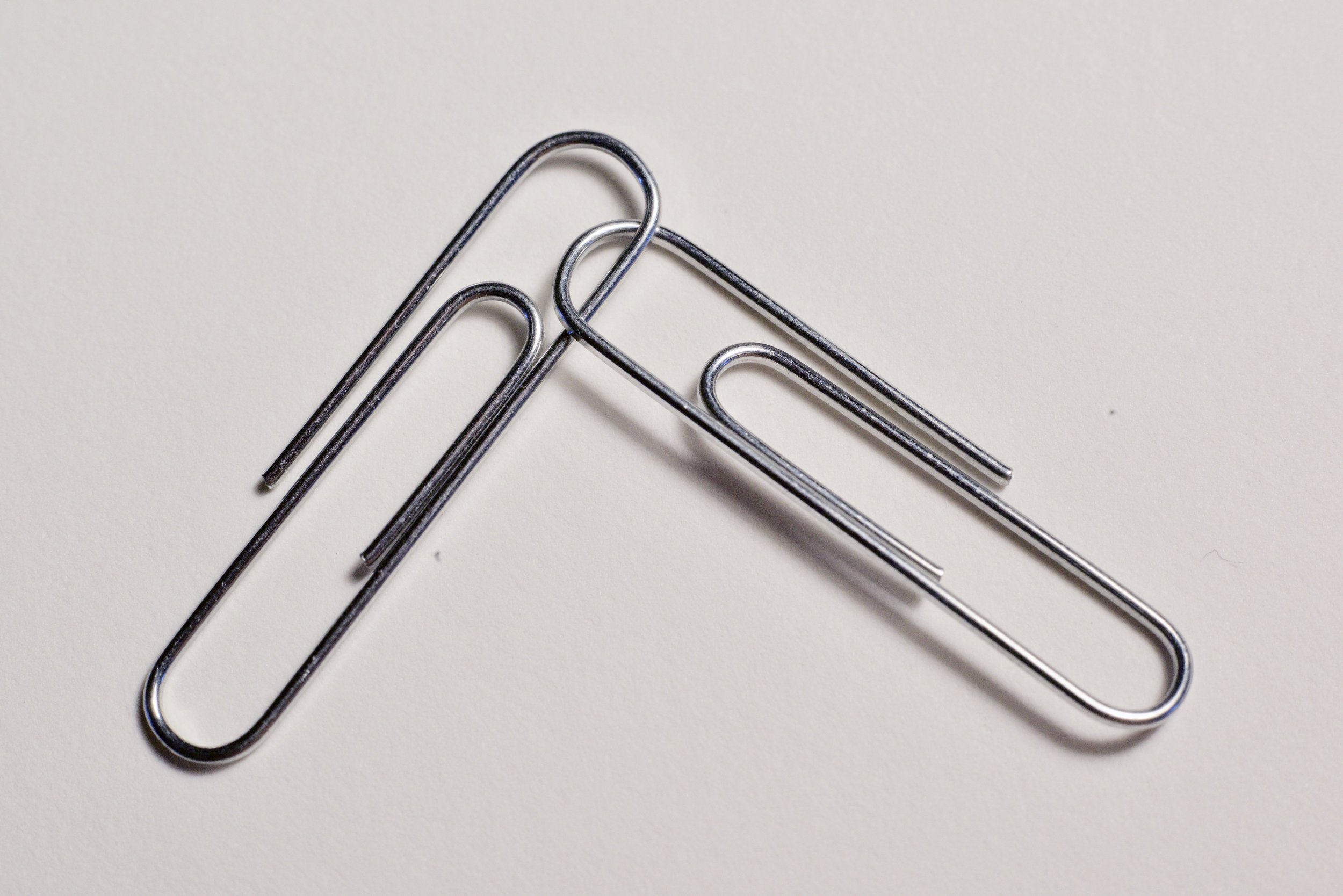

One of the triumphs of industrial design: the Gem style Paper Clip. It first appeared in the 1880s in Britain. In a world of ever increasing complication the Paper Clip is perfect for the job, simple and esthetically pleasing. Expect it to be replaced soon by the Smart Clip requiring a micro processor. Because we need that.

Words: Jerry Blanchard

After using a flip phone for over 20 years, I just got my first Smart Phone, an Apple SE third generation model. I have been using it to photograph engraved watches and other pieces of my work, and am finding if takes good photos to record my work, and I can also send photos as needed. The phone has many features not needed by or of interest to me, and I am working to learn how to use the new phone with ease and certainty.

I suppose Apple must appeal to a very wide customer base by jamming into the phone every conceivable feature they could think of in order to hopefully satisfy the needs and desires each one of the many millions of users. This must make those who love complexity for complexities sake happy, but I am not one of that persuasion.

There are some needs today that can only be met with extremely sophisticated and complex machines, for instance: medical radiation and imaging technology, control of aviation flight and weaponry, satellite communication, ground penetrating radar, DNA sequencing, and so many other fields. It is wonderful and often life saving to have such technology available to us, and I appreciate the brilliant people who have made such things possible. I appreciate complexity when it is necessary, but feel many machines and devices today have been made overly complex for the work they are to do.

There are likely several reasons for this: some customers are fascinated with complexity for complexities sake, and manufacturers use complexity as a marketing tool. An extreme example of complexity is self-driving vehicles, which seems madness to me, but the vehicle manufacturers may see it as a way to cut out the small repair shops and force buyers to use only the manufacturers for maintenance servicing. Another marketing strategy of manufacturers is constantly changing and “upgrading” in complexity as a way to force people to buy new things.

These days computer chips in their dozens and hundreds have been designed as critical parts of most modern vehicles. The chips are mostly made overseas and in many cases in countries that do not like America very much.

Many of you are old enough to know vehicles worked very well before computer chips were even invented, and chips are not really necessary to make fine running, dependable, and easy to service vehicles.

The use of chips in vehicles has some technical benefits of course, but that choice also brings a large downside that has in recent years been glaringly apparent when the chips became difficult to obtain, putting a stranglehold on American manufacturing. I remember the old quote by Charles ‘ Boss’ Kettering of General Motors: “ Parts left out cause no service problems”.

Our 1977 GMC pickup truck with 350 V8 engine had the fuel pump located on the lower right of the engine where it was easy to change when necessary. The pump was also inexpensive. Our 1998 Chevrolet pickup truck has the fuel pump located inside the fuel tank where servicing is a major job, and it cost $1000 to have it replaced. I am told the fuel pump is linked in some way with the truck’s computer, so installing a simple electric fuel pump outside the tank was not an option. This is just one example of complexity being used instead of good design and common sense.

I am one who loves brilliant design that is as simple and clean as possible commensurate with doing the work required. It seems to me that many machines and appliances in modern life are more complex than they need to be to serve us well.

I do not appreciate washing machines or dishwashers with a vast number of settings. How about keeping it simple with just a few settings: perhaps on, off, large load, small load? Things would be easier to use, less likely to fail, and easier to service. We have a Maytag washer that has run faithfully for over 25 years without needing any service. It has simple mechanical controls, no chips or computer, adequate options, and is quite wonderful.

I work with things as they are these days, but somewhat grudgingly tolerate many overly complex things in modern life because I have little choice.

The Eifel Geared Plierench. Designed in the early 1930s it is an example of flexible industrial design and quality manufacturing. Note the price stamped into it. All objects tell a story of culture and economics.

The bird sings for me in the finding and use of tools and machines often from earlier times when superb and elegant design was more common. A few favorites of mine are: my excellent Montblanc fountain pen that I have used for 50 years; fine shears for metal and cloth made by Wiss before the company was bought out by Cooper Tools; superb Eifel Geared Plierenches; Starrett, Brown and Sharpe, and Lufkin precision toolmakers instruments; excellent files, gravers, hammers, and other traditional tools of silversmiths and metalworkers; fine old handsaws, chisels, planes, and tools for woodworking; Snap-On, Proto, and Plomb wrenches and hand tools; my wonderful 1958 South Bend toolmakers’ machine lathe ( now with my son, Mike). These are just a few things I especially value for their elegant simplicity and usefulness,

“Keep it simple” should be the mantra of every designer.

Perhaps part of the reason I like certain elegantly designed and beautifully made tools, machines, and pieces of art is that I find the modern world complex, unsettled and often threatening. The world these days is so often not comfortable nor reliable, and is constantly changing and bringing new problems and impositions by the myriad layers of government, manufacturers, institutions, and officialdom in their many forms.

It is comforting to own useful and superbly made things that can be depended on for lifetimes of fine service, and for the joy of simply owning great beauty.

As a maker of useful art I use a great variety of tools, many of them traditional ones that would that would be familiar to artists of earlier eras. I find much pleasure in the making of things of precious metals, fine steels and other alloys, rare woods, and other fine materials, and the using of fine tools is part of the pleasure. The world may be rather a mess, but a finely made hammer, graver, file, chisel, or handsaw, especially one that has age and history, is dependable and elegant in its way, and such things make it possible to create lovely things, and the work can for a time push aside the stresses of the world.

For me, a smart phone, computer, electric chop saw, battery drill, most modern cars, and such things are certainly helpful, but they are designed for a limited useful life. In many ways they are just throwaway items one uses for a time and discards as they are rendered obsolete by newer varieties of throwaway items.

The sorts of things I value highly are the opposite of throwaway: they are things one can use for a lifetime and pass on to be valued and loved by others for their lifetimes; things like excellent hand tools of many kinds, art metal, furniture, and many other things of craftsmanship and beauty.

In this time of artificial intelligence and computer and robotic control of so many things that affect our daily life, I feel it is important to keep alive manual skills for fine metalworking, woodworking, and other areas of craftsmanship and artistry. Using hammers, files, gravers, and other tools as generations of artisans before me have done links me with the past, gives me great pleasure, and carries on the great traditions of craftsmanship and artistry long appreciated by people of discernment.

I know that not everyone feels that way, but there are still those who appreciate the difference between an item “engraved” by some robot machine versus being hand engraved. Many things are of course rightfully inscribed by machines, but special items of a personal nature like silver flatware, compacts, fine watches, rings and jewelry are best done by hand. Thankfully, there are still enough people who want hand engraving to keep me busy. “Made by hand” still carries a special cachet with many people.

I have spent long years of my life learning traditional skills so I can make art I choose, and I feel a responsibility to those who so kindly helped me learn those skills to pass on what I have learned to others who truly want to learn the art and mystery of some of the traditional practical arts.

One of the joys of my life now is to see my children creating with great skill art and craftsmanship of a wide variety.

For over a year I have been teaching hand engraving and silversmithing to a bright girl who just turned 11 years old. Such work is demanding and requires a high level of interest and discipline that few have, but this girl has the gift, and it is a pleasure to see her grow in knowledge and skills.

My mentors from long ago are in a way part of me, and when I am gone, I hope a part of me will live in others as they carry on traditions of fine handwork.