Nikon F

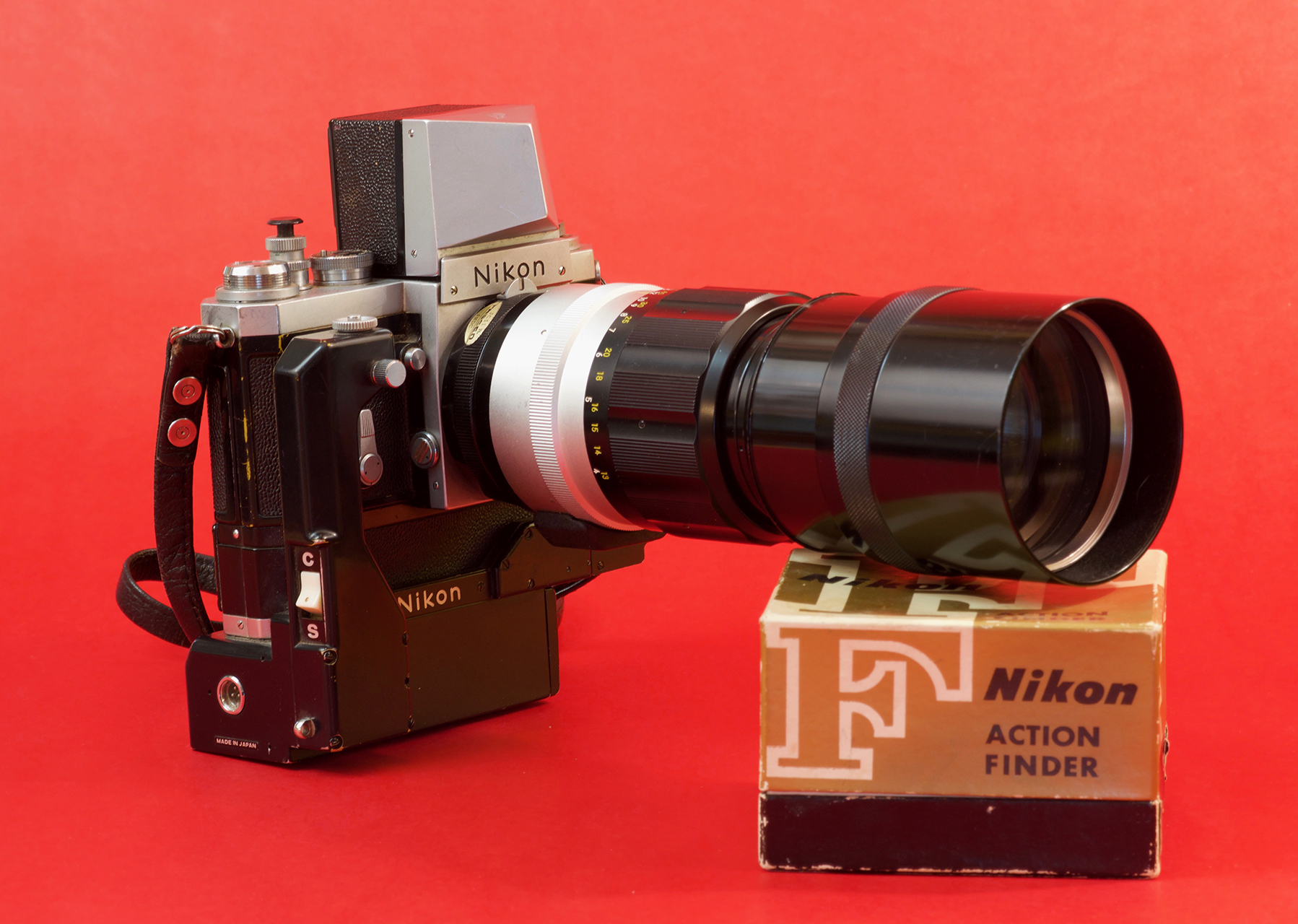

A good example of the versatility of the Nikon F system. A chrome body mounted with a Nikkor 300mm telephoto, an F-36 motordrive and the action finder. This was a popular setup with sports photographers. The modular nature of the camera made it a big hit with professionals who could count on the big Nikon in any situation. This 300mm lens is in mint condition and still has its inspection sticker intact.

Text + Photos: Mike Blanchard

Gear | For years my Nikon F camera was my most cherished possession. As a young photographer, I found the F represented the romance of the foreign correspondent and the quest for adventure.

The F was a star in the films “Blow Up,” “Full Metal Jacket” and “Apocalypse Now.” It hung from the neck of guys like Larry Burroughs and David Douglas Duncan. When Paul Simon sang “I got a Nikon camera…” he was talking about the F.

By the time I took up photography the F2 was Nikon’s top of the line, but for me it never had the romance of the old dog. There was a guy in Santa Barbara in the late ‘70s named Del. He ran a camera store (selling Nikon exclusively) out of his living room on Carrillo Street. The coffee table was like a New York skyline of lenses, and the bodies resided in a chest of drawers.

Back of the F-36 motordrive showing the speed options and the switches to set them. You have to reset the exposure counter to zero with each new roll before the drive will work. The box on the bottom is the battery chamber. This was the second version of the drive. The motordrive was an industry first for Nikon. There were several hand-operated speed winders available and a couple of motordrives on the drawing board, but Nikon was the first to bring it to market.

Del patiently put up with my teenage enthusiasm and my mom’s skepticism, and I got my first good camera as a graduation present. I have had a Nikon F ever since. Unfortunately, I don’t have the first one anymore but I still have the second.

Like the Colt Government Model, the paper clip or the Ford Model T, the Nikon F is an industrial product perfect for its time. Today this iconic 35mm camera still has presence, and 60 years after its introduction, it continues to be as good as any camera available. The thing was so “right” that it was essentially unchanged for 15 years in the cutthroat market for professional cameras.

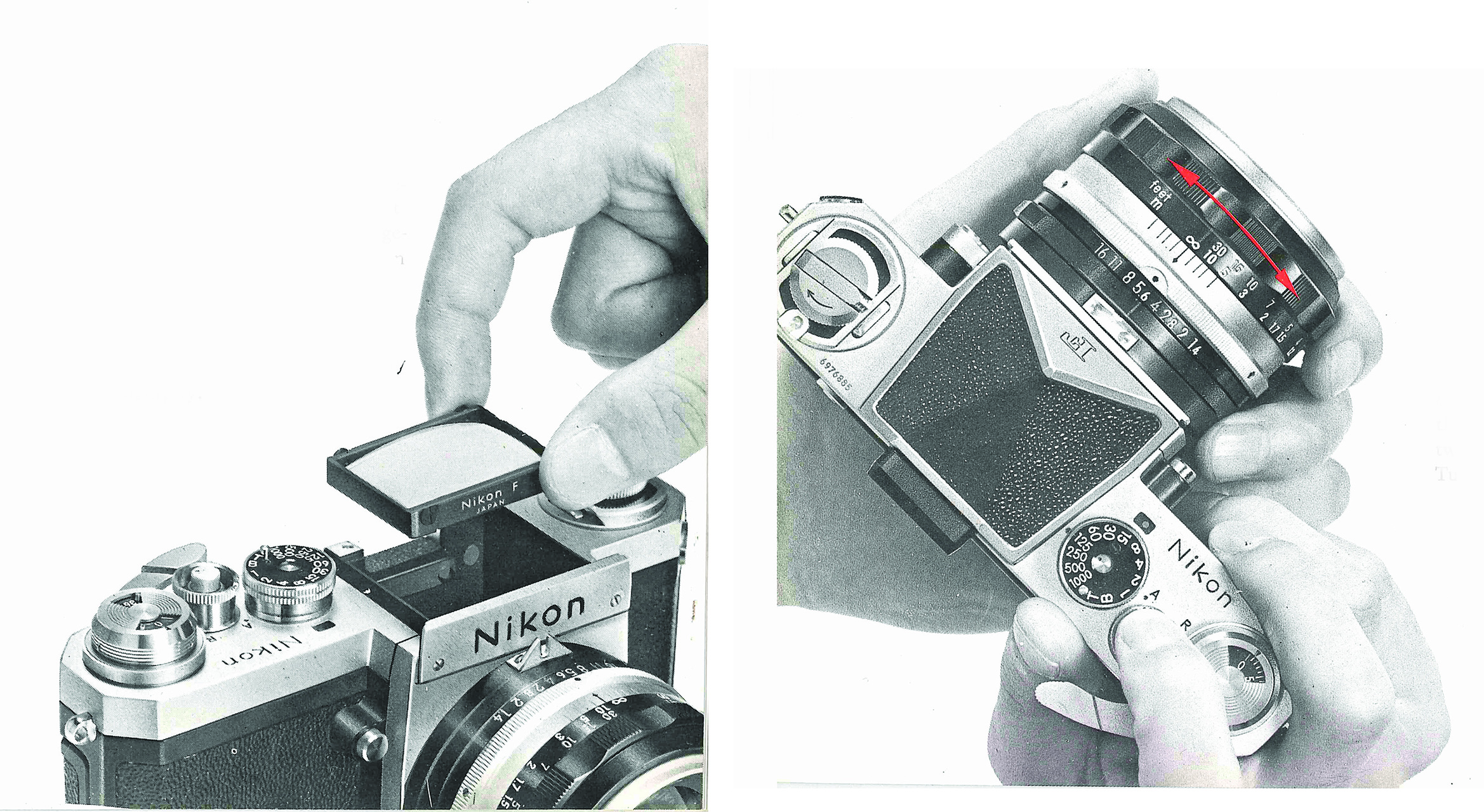

As good as it is, the F has a couple of quirks. You remove the back of the camera to load the film. This makes it easy to get the film threaded (a welcome change from Leica film loading), but it is sometimes a pain to hold the body and the back, and under pressure it can take a bit of juggling. Also, there is no built-in mount for a flash. You need an adaptor, which goes over the rewind knob, so you have to remove the flash to change film.

“The thing was so “right” that it was essentially unchanged for 15 years in the cutthroat market for professional cameras.”

But that said, the F is a tank and is rightly considered the first single-lens reflex (SLR) design to get it right. Nikon took all the good stuff that other companies were doing and combined them in one brilliant design that swept all before it and changed the photographic industry.

The Nikon F was made by the Nippon Kogaku K.K. company. The firm was formally incorporated in 1917 as a jointly owned company by the Japanese Imperial Navy and the Mitsubishi Trust.

In 1920 Heinrich Acht, a German optical engineer, was hired to help upgrade its designs. At the time, Japanese engineering took its cues from Germany.

Ironically, Nikon owes its camera business to Canon and Leica. In 1934 Leica patented its lens mount and rangefinder coupler in Japan. The Seiki Kogaku (Canon) company, which had been copying Leica, was forced to come up with a new design, and it approached Nippon Kogaku to produce a new lens, mount and rangefinder.

Kakuya Sunayama, the company’s head of design, laid out the optics and Eiichi Yamanaka designed the lens mount. This first lens, a 50mm f3.5, featured a bayonet mount with a focusing wheel and a pin-operated rangefinder coupling. Nippon Kogaku also designed the rangefinder mechanism. The system first appeared in 1935 on the new Canon Hansa camera.

Nippon Kogaku, a much bigger company than Canon, had a great deal of influence on the smaller company, and for many years Canon was in effect a subsidiary. They continued to make the optics for Canon cameras until 1948 when Nippon Kogaku introduced its first complete camera, the Nikon 1.

Between 1935 and 1948 Nippon Kogaku also made lenses to sell to the Japanese home market. At first they used the brand name of Nikko, which is a compilation of the first two letters of Nippon Kogaku. In 1936 the letter R was added to make Nikkor, by which name the lenses are still known. These lenses, mostly in the 39mm screw-mount format, became celebrated for their optical quality and robust construction.

A black 1974 Apollo body with a chrome eye-level finder. Collectors call this mix of chrome and black components a panda. This was the last version of the F body. It features the film advance and self-timer lever of the F2 Nikon. The lens is the super fast 55mm f1.2 Nikkor with matching lens shade.

After World War II, photographer David Douglas Duncan, who was in Japan covering the Korean War and Japanese reconstruction, purchased some Nikkor lenses for his Leica that proved to be very sharp, and he became an informal ambassador of the company’s products to the west.

Nikon debuted the F in April 1959 with a U.S. price of $186 with a 50mm f2 Nikkor lens. The F had been four years in the making. The project was started in 1955 with the first three prototype sets built in 1957. It was an evolution of Nikon’s successful SP/S3 rangefinder cameras. The mirror box and pent prism of the SLR were basically grafted into the rangefinder body. The lens mount was increased in size from 34mm to 44mm to support larger lenses.

The exterior design was done by Yusaka Kamekura and won several industrial design awards in the ’60s.

Prior to the Nikon F, the go-to professional 35mm camera was the Leica M series rangefinder. Leica had practically invented the 35mm camera and had held a strong position for almost 40 years. With a rangefinder, you don’t see through the lens. You look through a viewfinder next to the lens that uses a prismatic range-finding mechanism to focus the lens. They are small and quiet cameras, but they have certain limitations.

Rangefinders work really well with lenses from 28mm to 100mm in focal length. But super-wide and long telephoto lenses don’t work well. The big plus of the SLR is that you see exactly what the lens does. You’re looking through it. It is a very intuitive camera to use. The downside is that the camera is big for a 35mm camera and it makes a distinctive, fairly loud “clack” when you release the shutter, which can be a detriment in some situations. But those issues are common to most SLR-style cameras.

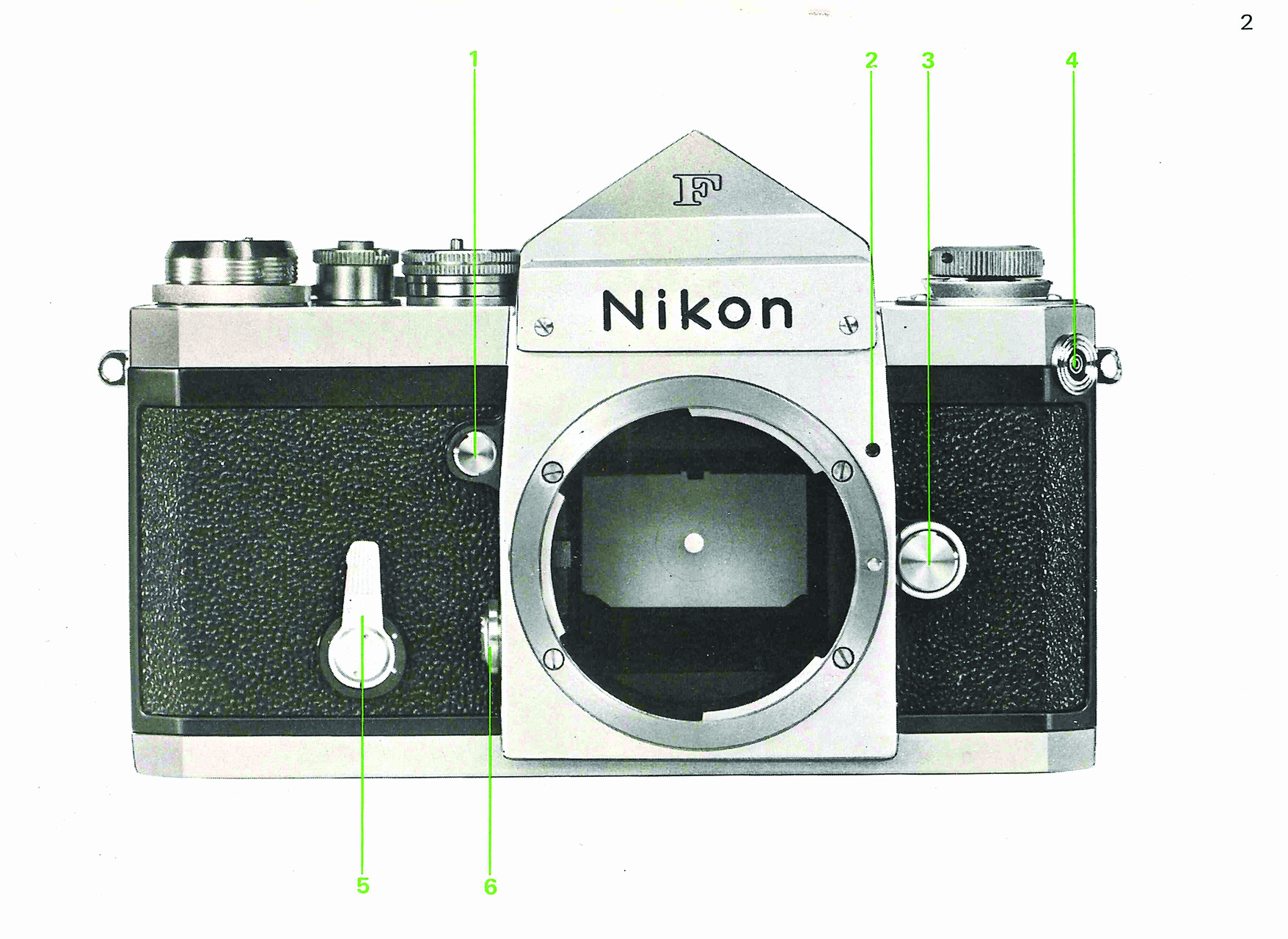

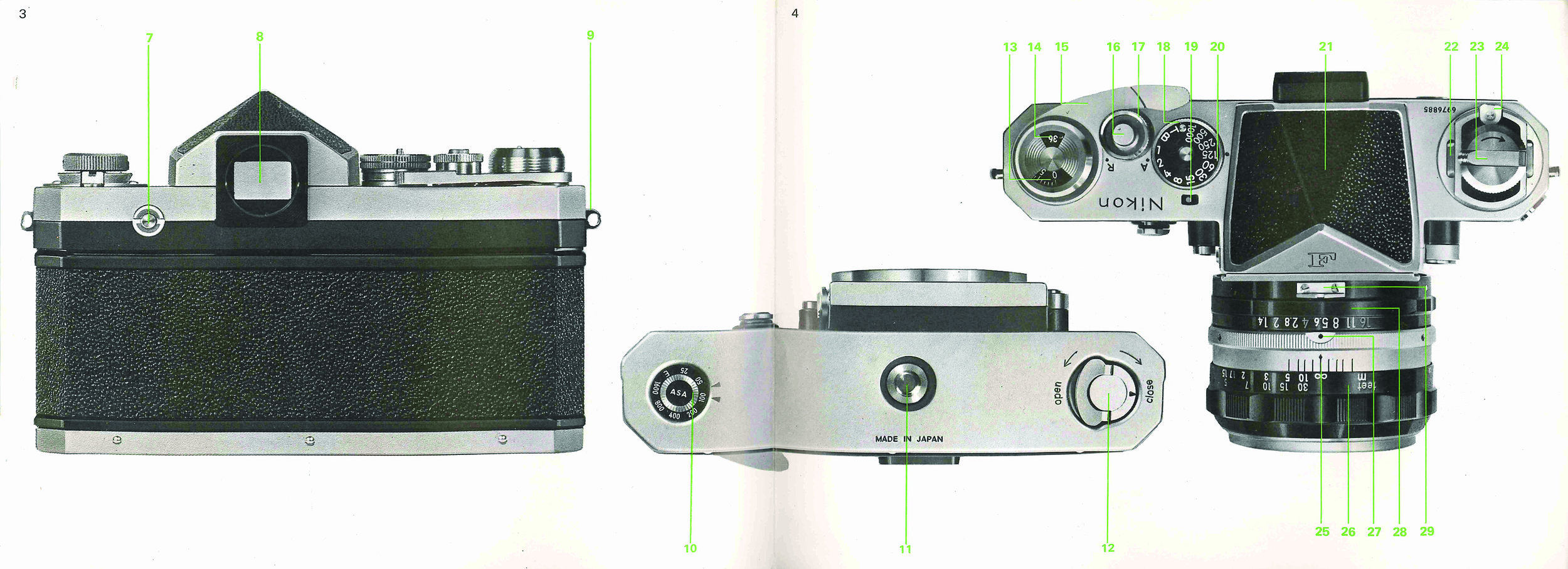

The F featured a number of technical advances that pretty much defined the layout of every professional SLR that followed. It had an auto-return mirror, a lockable mirror, interchangeable prisms and viewing screens, a depth of field preview feature, a 100% viewfinder, eyesight compensating viewer diopters, a clip-on light meter, a motordrive with several triggering options, large capacity film backs, a Polaroid back, multiple flash modes and a titanium shutter.

Another big feature of the F is that it was debuted as a complete system designed to provide the widest possible range of flexibility. You could use an F in every photographic situation you could think of, including going into space. The lens system ranged from a 21mm wide angle to a 1000mm telephoto. There were macro lenses, bellows-focusing devices for extreme close-up photography, shift lenses for architectural work, lenses specifically for the medical and dental field, products for scientific research, zoom lenses and many more.

There were four different viewfinders available. The basic eye-level finder, a waist-level finder, a large-screen action finder and the Photomic FTn metering finder. For many, the large, boxy Photomic finder defines the Nikon F silhouette.

Early on, Nikon offered a clip-on selenium cell light meter that attached to the top of the camera, but that was eliminated with the introduction of the Photomic finder.

Underneath the prism, Nikon offered 10 different viewing screens with different focusing aids or compositional aids appropriate to different applications.

The chrome action finder was one of four finders that Nikon offered for the F. It featured a very large viewing port so the photographer could easily see the whole screen even if the camera were held away from the eye.

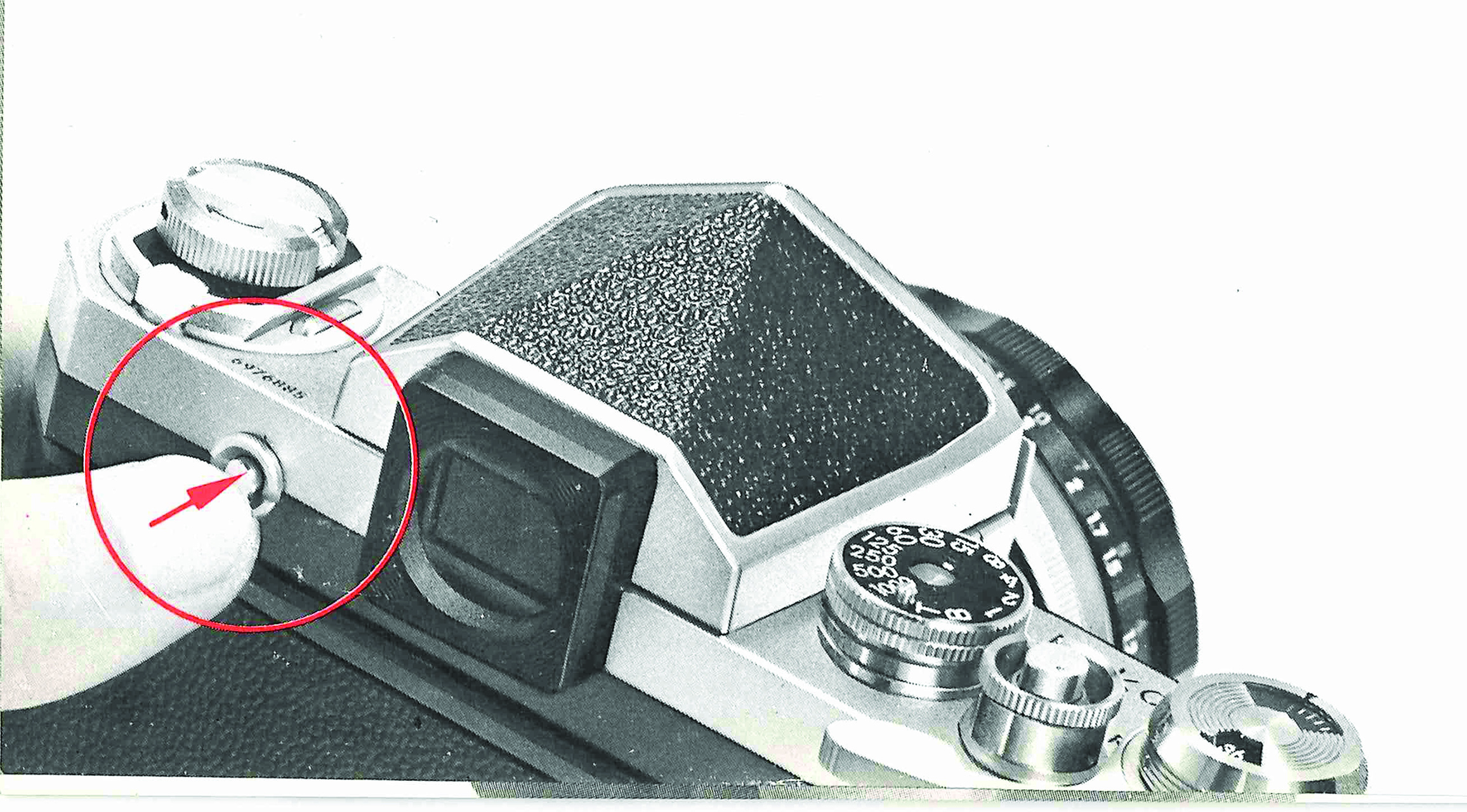

The F-36 motordrive was an industry first for Nikon. The first version came with a remote battery pack worn on the belt or a strap, with a power cord to the camera. Very quickly Nikon introduced an option with a trigger/grip assembly, and the battery pack attached to the bottom of the motor drive. The drive could crank out 3.6 frames per second, or faster if you lock up the mirror. Not all Nikon F bodies will accept the motordrive. The camera body must be modified with a specific internal base plate to accept the motordrive.

At NASA’s request, Nikon developed a special version of the F for use in space. It featured aluminum body panels instead of the leatherette, larger controls for use with gloved hands, special adhesives and lubrication that would not outgas in space, lenses with handles on the focusing and aperture rings, hyper-accurate shutters and NASA-approved, military-grade wiring in the metering and motordrive systems. Maintained by the factory, these cameras were used for more than 20 years by NASA.

The Nikon F was snapped up by professional photographers. They relied upon the rock-solid construction and ruggedness of the Nikons. The damn things just worked. New York camera repairman Marty Forcher famously opined, “It’s a hockey puck.” I have seen photographers hit people with a Nikon F and keep on shooting with no loss of function or light leaks.

“The pro war correspondent setup in the ’60s was an F with the 200mm f4, another F with a wide angle and a Leica M3 with a 35mm or 50mm.”

The F went to Vietnam, and every other conflict zone, and proved to be the camera to have for journalists as well as soldiers. Thousands were sold to GIs at the PX or in the camera shops of Japan and brought back to the States.

The pro war correspondent setup in the ’60s was an F with the 200mm f4, another F with a wide angle and a Leica M3 with a 35mm or 50mm. You will see this over and over in photos taken of press photographers during the period. Of course this was in an era when zoom lenses were junk.

Sports photographers took to it because the motordrive and long telephoto lenses enabled them to get shots that had never before been possible. Scientists and the medical industry used them because the camera’s through-the-lens viewing and close-up capabilities assured that they could accurately document their work.

In terms of the camera industry as a whole, the Nikon F marked the ascendance of the Japanese camera manufacturers over the German makers. Leica and Contax (and to a certain extent Rollei) would never recover the market share they enjoyed before 1960. In the mid-‘60s, Nikon ran an ad for the F that said, “Today there is almost no other choice.” And it was correct.

These days we have many fine choices for 35mm SLR cameras. In most instances the only advantages they enjoy over a Nikon F is their light meter and their weight. With the recent upswing in film camera popularity, and prices, the F seems to have been happily left a bit behind.

Good used Fs are available for under $300. Rare models, black bodies and mint examples, bring upwards of $1,000. Non-AI F series lenses are cheap as well. World-class glass like the 105mm f2.5 is available in the $100-$300 range. Clean 50mm lenses can be had for under $100.

The eye-level viewfinder is probably the most desirable option when buying a used Nikon F. It’s simple and good looking with nothing to go wrong. Many of them have a dent of some kind, but most of the time this will not affect operation. Oddly, it can be more expensive to buy an eye-level finder by itself than it is to buy a camera body with one attached. The Photomic FTn is a more sophisticated prism, and is quite common, but frequently the meter is dead and I am not sure there are parts for repair anymore.

The F serial number range starts at 6400001 with a total run of 862,600 bodies made in a 15-year manufacturing run. The F was succeeded by the F2 in 1972 but was being sold by Nikon until 1974.

There is a bit of a myth that the first two digits of the serial number are the year of manufacture. This is true for 1967 and later bodies, but only by coincidence and it’s a bit loose. You should check a serial number list to confirm YOM.

There are those who will maintain that the German (and Swiss) cameras of the period are better than the Japanese offerings. I think there is a bit of jingoism or snobbery in the claim. The Leica M, Alpa SLRs, Contax SLR, Canon F-1 and the Nikon F are probably all in the running for the best-engineered 35mm camera in the ’60s. But this question of what is the best is a bit of a red herring and misses the point.

The Alpa and the Contarex were both well-made but really wonky, and they never enjoyed widespread popularity. The lenses were/are very expensive and hard to find. They were cameras for a very few well- heeled camera nuts. Except for the fact that it is rather expensive, I can say nothing against the Leica M. I will say that as a rangefinder it is not quite as versatile a camera as the Nikon. The Canon F-1 is very similar to the Nikon, and quite well made, but it was never as popular.

There is little in terms of engineering quality between any of these cameras. It is just that the Nikon F was exactly what professional photographers wanted. It dominated the market and became a cultural icon in the process.

I don’t see many Nikon Fs hanging on people’s necks these days. For a camera that was at one time synonymous with 35mm cameras, it is curious. On the other hand if people are not snapping them up like crazy then they will stay cheap. The F is one of those things that is a conversation starter. People will say, “I used to have one of those,” and tell you about it. I love to hear those stories.