Craig Vetter: Designer, Entrepreneur, Racer

Interview: Mike Blanchard

Feature | Craig Vetter is doing better. On August 12, 2015, he hit a deer about a mile from his house in Carmel Valley while riding his fully streamlined Honda Helix. He suffered a traumatic brain injury and required three rounds of brain surgery to survive it. The wreck has understandably slowed him down. However, in the last nine months, with the help of his wife Carol and sons Zak and Morgan, he has made remarkable progress and is back working on his biography.

Vetter, 77, is one of the seminal American motorcycle designers and stylists of the 20th century. At one point, the Vetter Fairing Company was second only to Harley-Davidson in the U.S. motorcycle market. His hugely successful Windjammer series of fairings alone would give him a place in moto history. When you add in his brilliant 1969 redesign of the BSA Rocket lll, which appeared in 1972 as the X-75 Triumph Hurricane, and then throw in his redesign of the oil-in-frame Triumph Bonneville, we are talking about design greatness.

Vetter was a pioneer in so many ways. When he started making fairings in 1966, he was one of the first people to even build fairings in the U.S. His early fairings, the 500, 600, 800, 1000, 1500, 1600, 2000, 2500 and Phantom series, are coveted collector items. The Windjammer and the Vetter-designed luggage kits set the stage for the whole world of touring motorcycles as we know them today. Honda took one look at what he was doing and got him to design fairings for them.

Vetter and the Rickman Kawasaki on which he came third at Daytona in 1976. Vetter was the U.S. Rickman importer from 1973 to 1976. Photo courtesy of the Vetter archive.

From 1966 through 1983, when he sold his company, Vetter was at his most prolific. He was the importer for Rickman motorcycles. The output of the Vetter Fairing was doubling in size almost every year. He designed and put into production the outrageous Mystery Ship hot rod bike. In 1980 he crashed his ultralight plane and broke his legs. In response he started a new company, the Equalizer Corp., and designed very successful racing wheelchairs. He took his knowledge of fiberglass and started a company making hot tubs and spas. It just goes on and on.

And he raced. Riding a Rickman-framed 1100cc Kawasaki, he came in third at Daytona in 1976 in the amateur production/cafe racer class. Later in ’76, Vetter came off his RD350 in a race at Road Atlanta and suffered significant leg injuries. He returned as a team owner in 1978 with Reg Pridmore riding the Vetter Kawasaki and won the AMA Superbike championship. Pridmore rode the team’s Pierre Des Roches-tuned Kwaka in ’79 as well.

In 1980, Vetter began devoting himself to streamlining motorcycles for speed and increased fuel economy. The Vetter Fuel Economy challenge is recognized for pushing the limits of hyper-efficient motorcycle design. His Rifle fully streamlined motorcycle fairing is still available. He is very interested in electric motorcycles. His son Zak is actively involved with a company working on electric motorcycle chargers, and Vetter is keeping a fatherly eye on the work as it progresses.

I ran into Vetter at the Quail Motorcycle Gathering, and he graciously invited Rust to visit his home and workshop to talk motorcycles and design.

Vetter started right off with his story before we asked any questions. And it is a remarkable story.

Craig Vetter: “Three years ago I hit a deer. I had no memory of the first two years. They didn’t know if I was going to be walking or talking or thinking. I’m still working on it.”

Carol Vetter: “Our two sons have played a huge part in his recovery, and the doctors are amazed. They did three operations on his brain, and each time they were operating on him they said, ‘Well, you know, I’m not sure if this is gonna work.’ I said, ‘He’ll be fine; he’ll be fine,’ and he was and he’s coming back stronger than ever.”

Craig Vetter: “So you got a very different kind of a person than I was three years ago. Three years ago I was on the top of everything and that’s what I wanted. It’s not that way anymore. Probably the biggest thing that is different is God is now the top of my life. It’s not Craig; it’s God. That’s the simplest explanation. It has a lot to do with what I’m doing and what I’m going to do. … Without Carol and our two boys I’d have been dead, just down the road within a mile of here.”

Rust: One of the things I am impressed with is how relevant the Vetter fairing, the Windjammer fairing, still is. It elicits strong feelings one way or the other. Some people hate it; some people really love it. It’s become an industry icon. How do you attribute the fact that it is still such a relevant thing and it hasn’t even been produced for 30 years?

Craig Vetter: “It solves a real problem. And it also looks good. And also it’s made better than anything you can imagine. It was made to last forever and it was never intended to get old. It was never intended to run out. It was always intended to do more with less energy, more with less effort. Which is a characteristic of my life. Characteristic of my life is to be involved with things that do more with less. What I just told you can’t be repeated by anybody because no one understands it. (Laughing) You can write it but can you understand it?”

'70s horse power, the Mystery Ship hot rod face to face with the Vetter Kawasaki which Reg Pridmore rode in the AMA Superbike championship. Photo courtesy of the Vetter archive.

Rust: More with less.

Craig Vetter: “Yes, more with less. So you want to know why the Windjammer is good? The Windjammer did and does everything that I wanted it to do. And it looked good and lasted.”

Carol Vetter: “You know I still sell parts. I’ve got a shipment for Norway. I still sell parts all over the world for those things.”

Rust: Do you ship them from here?

Carol Vetter: “Yeah.”

Craig Vetter: “There is little parts that go bad that we sell.”

Carol Vetter: “We sell the trim. We stopped selling the windshield because we were worried about a lawsuit. Windshield bolts, graphics for the side, tape for the windshield, snap vents. That kind of stuff. We sell it all over the world; it’s a riot. And what’s really fun is we know some of these guys. They’ll say, ‘You know I was out at the factory …’ It’s really fun.”

Rust: I love the part of your website that is all of your customers who have sent in pictures and letters talking about their fairings and their experience with it.

Carol Vetter: “Isn’t that fun?”

Rust: It’s addictive to go through that and read each of those guys’ stories.

Vetter: “Here is the thing. All my life I’ve kind of had a plan and the plan was to design and make the best things and they would all have a certain characteristic. They would do more with less. And I would end my life with a book. You know, I have been writing it for 10 years. Except two of the last years I couldn’t even think or read. So now I am back working on the book. It’s really all I do because I can’t work with my band saw.”

Rust: As far as design goes, I think you are one of the great American designers.

Vetter: “I do, too. I always did. Almost everything I’ve done, nobody has been interested in. Nobody thought it was worth any time at all. The motorcycle fairings, the redesigned triple, the redesigned Bonneville, redesigned wheelchairs, redesigned hot tubs. All these things. And racing, you know. I was a road racer. All those things. Most people, they don’t understand why I do those things. They don’t understand why I’ve done what I’ve done. Later on they think, ‘He’s rich and famous.’ That was never a goal. To do more with less has always been the goal.”

Rust: It is such a strong mantra throughout your work. When did you develop that concept and that saying, the philosophy of doing more with less?

Vetter: “It came out in school and shortly after school. I used to go to design lectures and I came across probably the greatest designer in the world ever. I learned that he was and I started to attend his lectures. I called him up one night at one in the morning. I called him up one o’clock or so and I said, ‘Is this Bucky?’ Buckminster Fuller was his name.

He is, as far as I’m concerned, the greatest inventor, designer, thinker the world has ever made. I was thinking of a better way to build a tetrahedron, and I said, ‘What do you think?’ and he said, ‘Oh, it’s a great idea.’ So we had a nice little talk. The guy was already older than me right now probably. (chuckling) He was the guy who said, ‘Do more with less,’ which I liked a whole lot. It verbalized something I was thinking. I was just fresh out of school; no one ever taught it to me, but it was something I thought was important.

I went to see him at a design conference at Aspen maybe six years later. Aspen is a big design conference in Colorado and I would go to it every year on my motorcycle. It’s like 1,300 miles from where I work. Buckminster Fuller was the big speaker that year.

People were asking him about himself, and one of the things he said was, ‘I like to do this; I’m a designer, but let me ask you, please, do not call me after midnight. (laughing) He said, ‘I had students call me after midnight years ago and ask me questions about designs. I love to talk about it, but I also love to sleep.’ I was going to sneak out the back 'cause it was me he was talking about and he remembered it.”

Rust: One of the things I like about your designs is that you obviously took into consideration aerodynamics. The most pointy-looking motorcycle, the raciest looking motorcycle has the worst aerodynamics. A bus had better aero than a GSXR.

Vetter: “It’s real simple. In 1957 the FIM, they controlled all motorcycle racing in Europe, and fairings had got to the point by 1956 or so that they were becoming aerodynamic. Round in the front and pointed in the rear. And as they did they were going faster and faster. These things were going so fast with their little engines that drivers were getting scared of them. They were on tracks that were not designed for 130 miles an hour. No one ever did it. Their cambers were off and they weren’t smooth and the tires on the bikes were never set up for 130. The track people didn’t want to change their tracks. The bikes themselves weren’t up to it. They didn’t have the right tires; they didn’t have the right brakes; they didn’t have the right engine cooling. What did they do? They just cut away the streamlining.

“These things were going so fast with their little engines that drivers were getting scared of them. They were on tracks that were not designed for 130 miles an hour.”

That’s when real streamlining was made illegal. It was not even done in America. When the AMA was authorized to be an FIM rep in ’62 or ’63, that was the first time that fairings came to America. We didn’t race with fairings. There was one guy down in L.A. that made a few but no one wanted them because no one believed in them. No one had any idea.”

Rust: How did you make the leap to working for Triumph?

Vetter: “They called me. I had designed this really neat seat/tank for my Suzuki 500. It was real long, held about six gallons. I parked it and one of the Triumph guys said, ‘Could I buy your new 1600 fairing for my Triple?’ I said, ‘Sure. What are you going to do with it?’ He said, ’I’m going to drive it to Daytona. You ought to come down, too.’ So I went. This guy from Triumph, he says, ‘Where you want to park?’ I said, ‘You know, I’d like to park down there where all the race bikes are.’ He says, ’I do that, too; come park with me.’ So I have this picture of my Suzuki with his Triumph with the fairing on it all surrounded by Gary Nixon and Gene Romero.

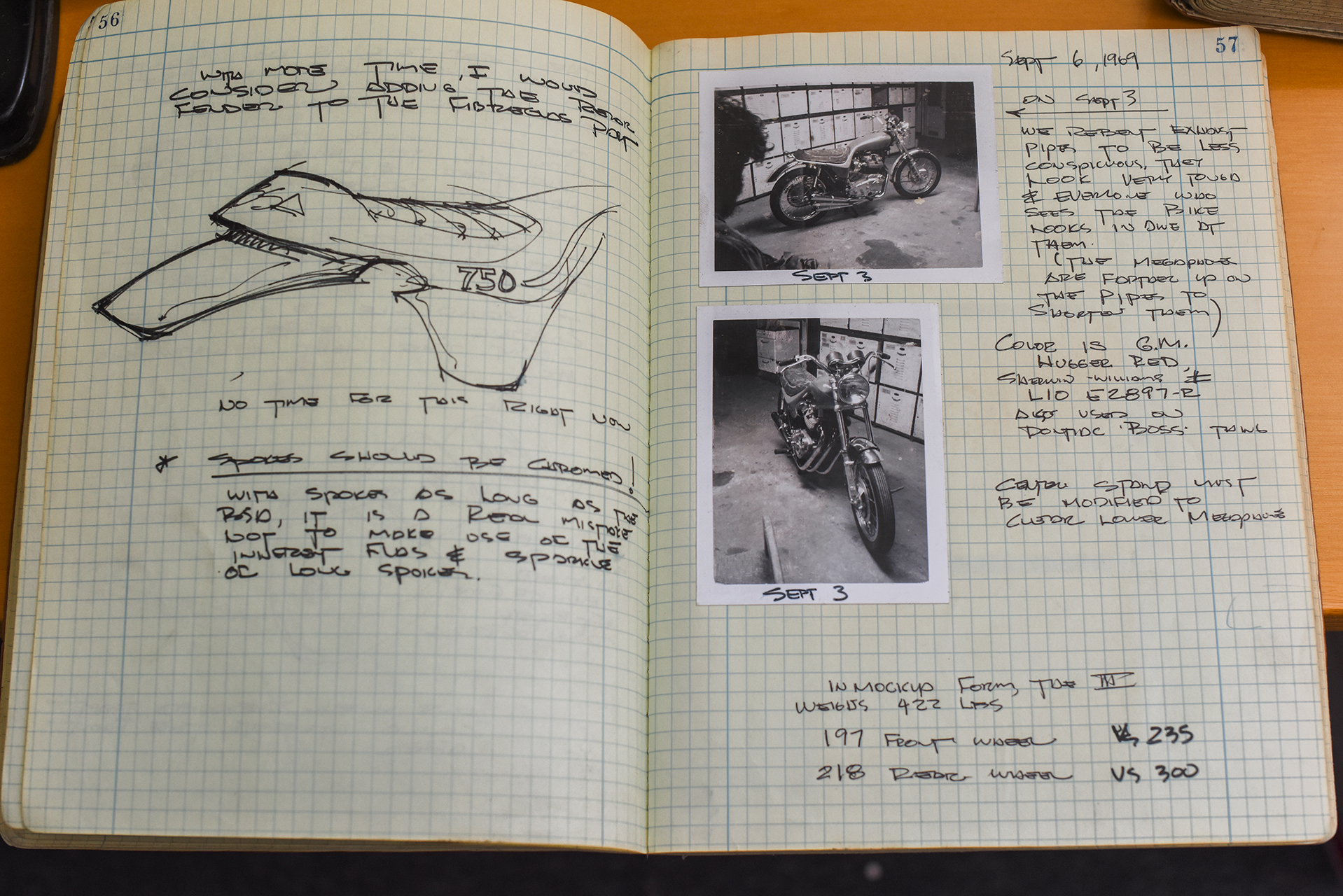

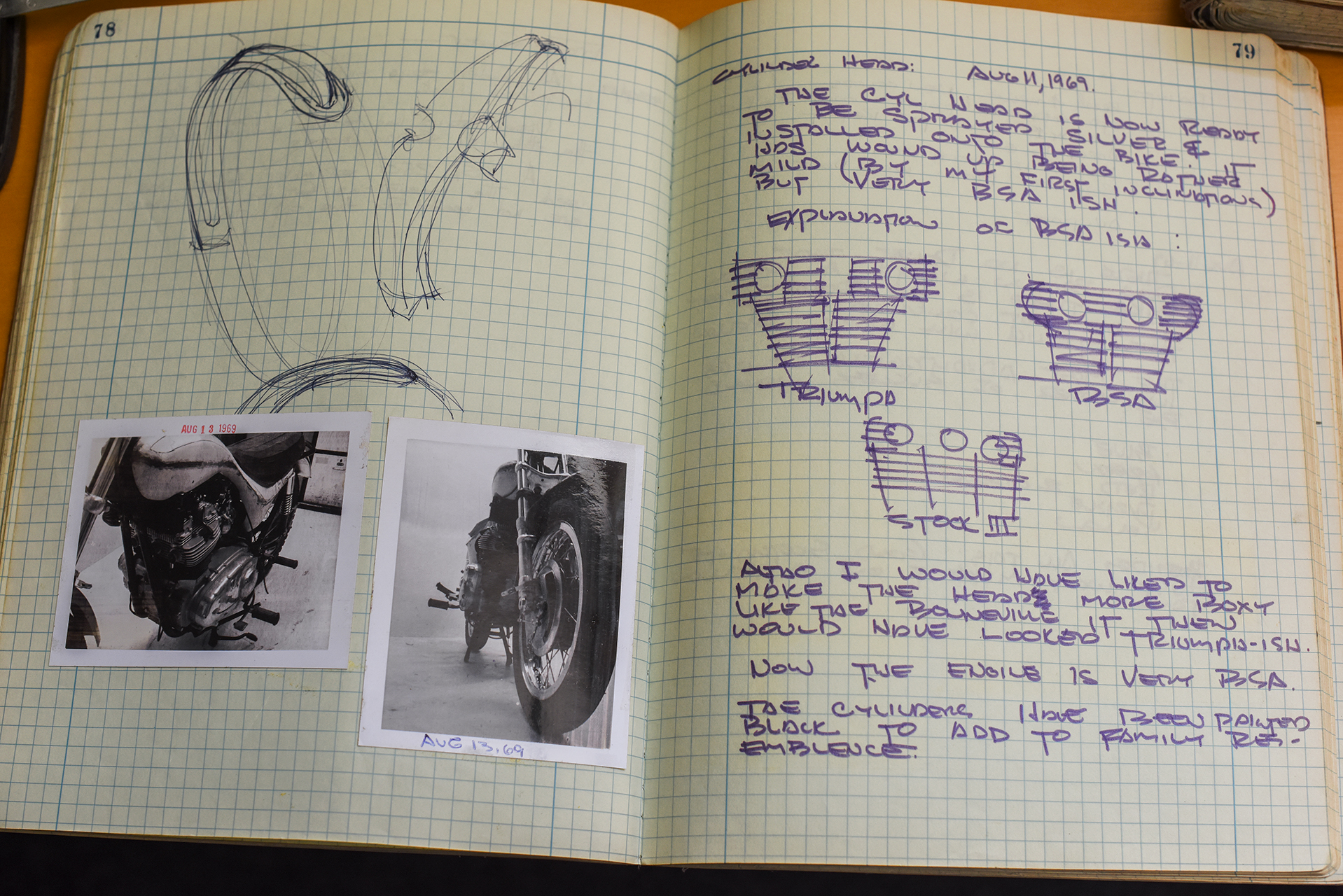

One of the salesmen from Triumph saw it and, I wish I could tell you his name, and he was stunned by it and he talked to his boss, Don Brown. Brown was with BSA and this other guy was with BSA, too. And he said, ‘Boy, I saw this thing that a guy had made for his Suzuki; it was really neat.’ And so Don Brown was kind of a free man at BSA and he was in charge of their sales, but he could see that what BSA was selling, was bringing to America; it was missing a little bit of what Americans wanted. Not really on. He told me that the designers at BSA, they don’t really, they don’t get what we want here.

Don Brown called me three months after Daytona and said, ‘Come out and visit me.’ He said, ‘We want to know if you can design. ‘We’ was him; it wasn’t anyone else; it was him. He said, ‘I want to know if you can turn this BSA Rocket lll into a bike that Americans would want.’ And it was private. Even though he gave me a bike, a Rocket lll, to drive back to Illinois. It was a terrible bike. There were good things about it, but mostly it was big and heavy. You sat up real high with it. It was very European.

The bike had been done by a company called Ogle Design in England. They did the BSA and they did the Triumph triples. So I drove it back to Illinois and went to work on it. What I wanted to do was Americanize this English motorcycle. ‘Cause the engines were neat, you know, and the frames were OK. It was the end-time look on the thing.

Ogle had done this look to it. So I just threw that stuff away and made it what I thought was very American. It was radically different. It wasn’t anything like the original Rocket lll. The original had a square gas tank and a giant square seat.

No American liked it. Nor did I. I built a very American motorcycle shape, American seat, very American about how we like to ride. The British would ride this way, OK? (drawing a straight horizontal line in his notebook). You have the seat, side and tank. Americans always like this (draws a shallow V). We always sat low in the center with the forks out like this. The Europeans like straight. They always did straight stuff. Whereas Americans, we like Harley-Davidson; we like this (pointing to the V shape).

“The younger the person the more they liked what I was bringing them. They saw it.”

Sunny Barger and I had a long talk one time about how this happened. It was basically his guys that went and bought tired Harleys from the police departments and little by little lowered the center and put longer front ends on it and gave them this look. This look has become American. So basically the Rocket lll is just an Americanized triple. Made out of shapes that Americans think are good. I’ll tell you the best tanks were Indian and Harley; they always have been. They’re round at the front and pointed at the rear. They are the shape.”

Rust: So when you did it what was their reaction to it in England?

Vetter: (laughing) “The young people loved it. See, the Triumph factory in England was a real sad situation. At the very top were guys in three-piece black suits who came to work in Rolls-Royces or Bentleys. They did not ride motorcycles. And when they went out to the factory they didn’t really want to go out there. In the factory were a bunch of guys that looked just like me. They had long hair and Levi’s and stuff and they looked just like me. The younger the person the more they liked what I was bringing them. They saw it. The older persons thought that I had brought in some kind of hippie-design stuff that was going to come and go. It was not going to be around. Whereas they were doing classic stuff that had been around forever in England.

So their first reaction was, 'Never seen anything like this. ‘This guy’s got long hair and he’s, what’s he doing this for? It’s not real.’ I thought it was real. It took the best of England and the best of America and combined them into a motorcycle that was basically a production chopper-esque motorcycle, even though I don’t like choppers.”

Rust: How did the Mystery Ship come about?

Vetter: “Mystery Ship first came about in ’73 or so. It was very early in my business. The idea was to develop the dream touring bike. The dream touring bike would have the dream look and be comfortable and stop the wind. It had everything streamlined and it would be the ultimate fairing for crossing the country. I fussed with it and fussed with it. I have pictures and sketches of all this. Making fairings, staying current with fairings; I was doubling every year, was taking all my time. So even though I wanted to make the dream touring bike, it was not important enough to spend all my time doing. It was interesting how in ’75 we became Rickman’s American dealer. The word was that they just handled really well. So I began doing Mystery Ship stuff on the Rickman frame.

Craig Vetter in his shop with the iconic Windjammer SS fairing. Still one of the very best touring fairings available. You can still buy trim pieces for the fairing from Craig Vetter.

In ’76 I crashed on my Yamaha in Atlanta. It stopped me from racing. I got third at Daytona that year. The Rickman was a racer, not a touring bike, but nonetheless it is associated because people think, ‘A touring bike? That guy’s a racer; this ought to be really good,’ which is what I thought, too. So I didn’t do anything on it for a couple years. I started again on it when I moved to California. I decided now the Mystery Ship would not be a touring bike, it would be a combination racer and street bike.

I talked to Derrick (Rickman) about it. I already had a racer so it wasn’t much to talk about. It was going to be Rickman (frame)-based and a street hot rod is what it was. It was going to be based on a Kawasaki, which were 903s to start with and became 1000s in no time at all. I was now living in California and I had a lot of West Coast contacts that I had made over the years. I was in San Luis and I’d go see Sandy Kosman, who was a frame maker over here, and let’s see who else, and Darryl Bassani, who was doing exhaust pipes, and Harry Hunt, who did aluminum discs, and Tom Lester. He was making aluminum wheels so I put aluminum wheels on ‘em. Oh, that’s not true. I was going to but I put alloy mags ‘cause they were real, real light. So this Mystery Ship was like a one-person street bike. It had a good fairing on it and good streamlining but it was clearly a race bike that you could ride on the street. It had lights on it.

“With that streamliner I began my Craig Vetter Fuel Economy Contest. That streamliner is now at the hall of fame museum in Ohio.”

I made 10 of them. So I kept track of who they went to. Malcom Forbes got two of them. I kept No. 1. The rest of them went all over the country. Then that was the end of it because at the end of ’78, somewhere in there I had another crash. (laughing) I had a hang glider; I was over in Victorville, and I was taking off. Didn’t know it but there was a freak rotary thing that came in behind me which I didn’t see ‘cause I was going the other way. I took off and I started going around. I did what I could. The wing caught and threw me to the ground and that was the second accident. (laughing)

Vetter inspecting his damaged Yamaha RD350 after his crash at Road Atlanta in 1976. Photo courtesy of the Vetter archive.

So I quit the Mystery ship and decided to make wheelchairs. Really, really exotic wheelchairs. After 10 Mystery Ships that was it. One of the magazines did a test, Bimota against the Mystery Ship. I think they liked the Bimota more because it had more hand-built parts on it, but they liked them both. One was very European and one was very American.

Rust: When you did it, did you do any aerodynamic testing? I’ve seen pictures of you doing tuft testing and things like that.

Vetter: “Not with that. I already knew; I already understood how important streamlining was going to be. It was not going to be that important. Because what was important here was making a really fast, reliable, good-looking, ‘Wow, look at that!’ street hot rod. That’s what it was. So the whole idea of going in a wind tunnel and making teardrop-shaped streamlining was not a part of that.

In fact, the teardrop shape on a motorcycle was never a part until the following year, ’79, when I made the first streamlined motorcycle based on a Kawasaki two-stroke. That was truly a streamliner. With that streamliner I began my Craig Vetter Fuel Economy Contest. That streamliner is now at the hall of fame museum in Ohio.”

Rust: I recently saw a red turbo Mystery Ship that was for sale.

Vetter: “Yeah; I saw that, too. It went to a dealer in North Carolina, I think. Mostly dealers bought ‘em cause they had a lot of money. A $10,000 motorcycle was probably going to be worth more someday. The last one sold at the Las Vegas auction for $30,000.”

A lineup of Triumph Hurricanes capped by one of two turbo charged Mystery Ships. Only 10 of the of the Kawasaki based bikes were ever made. At the rear of the lineup is a BSA Rocket lll, the bike Vetter was asked to redesign to create the Hurricane. Photo Courtesy of the Vetter Archive.

Rust: Did you have a problem with lift on the thing?

Vetter: “I never had a problem with lift. But Wes Cooley was riding with me down at Riverside. We had it down there and I wanted to see what real riders thought about it. Wes Cooley was one of the real riders at that time... His comment was, ‘Craig, I think you have some lift in this thing.’ My next job was going to be to figure out how to make that go away and still keep this aggressive kind of a look. But I just gave it up. I gave the whole Mystery Ship up. It was going in the wrong direction.

I didn’t want to do any more outrageously powerful, outrageously fast motorcycles. There is no point to it. That was the end of it. It didn’t start out that way. It started out as the ultimate touring bike.”

Rust: At road speeds it was fine.

Vetter: “Oh, yeah. We’re talking about going around the track at 130-150 MPH. No one was going to race it. It was never designed to be road-raced. It was designed to be, ‘Wow! Look at that!”

Rust: I think you achieved the ‘Wow!’

Vetter: “Yeah, yeah. It’s mine and I drive it.“

Rust: Do you still have one?

Vetter: “No, I gave it to the Hall of Fame.”

Rust: It is such a statement motorcycle. I think it’s cool that you only made 10 of them.

Vetter: “Well, I was going to make 100 but I ran out of energy.” (laughing)

Rust: I am interested in what your opinion is of the motorcycle’s future in a world of autonomous vehicles.

Vetter: “Autonomous vehicles? You mean self-driving cars? Here’s the way I think. Whatever the future is for motorcycles is the same as it will be for cars. I am never happy when our leaders, our controllers, want to take our control and take it away from us. I don’t like it. It’s all about control.”